OPINION PIECE

***ENGLISH VERSION BELOW***

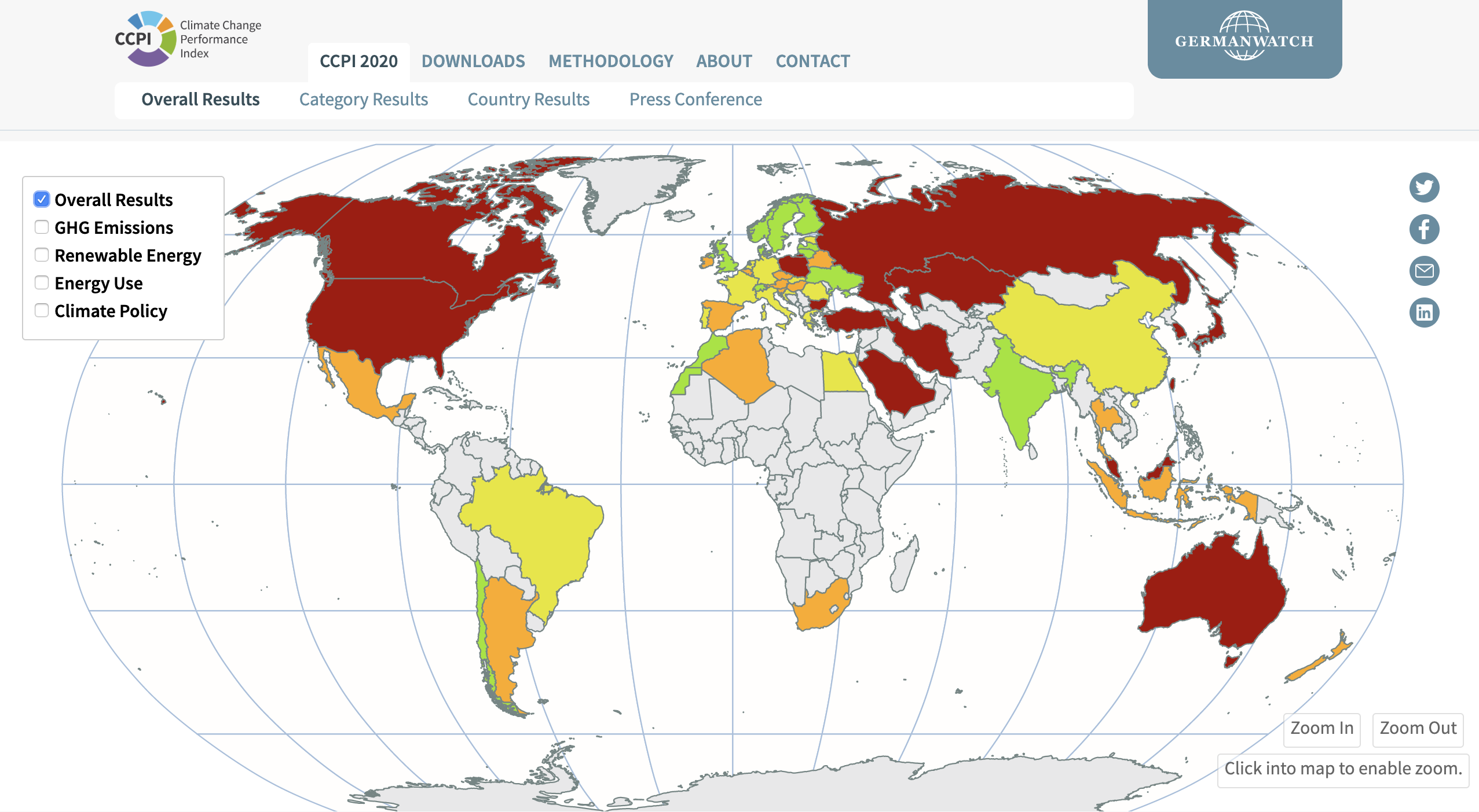

Image and data source: https://www.climate-change-performance-index.org/

Optimismus und Hausverstand in der Klimapolitik

Österreich schneidet in Sachen Klimaschutz bedeutend schlechter ab, als seine europäischen Nachbarn, und liegt laut CCPI sogar hinter China. Ist eine „optimistische Klimapolitik mit Hausverstand“ weiterhin gerechtfertigt?

Österreich ist, laut des kürzlich veröffentlichten CCPI (Climate Change Performance Index), in Sachen Klimaschutz auf Platz 38 abgerutscht, und liegt damit hinter China und weit unter dem Europäischen Schnittwert. Eine adäquate Klimapolitik muss, wie schon von Bundespräsident Alexander Van der Bellen betont, Priorität der neuen Regierung werden. Sebastian Kurz verteidigte seine Position, im Bezug auf die nationale Klimapolitik, bereits während seines Wahlkampfes wiederholt mittels der Begriffe „Optimismus“ und „Hausverstand“: Ein Hausverstand, der in der Lage sein solle, Wirtschaft und Ökologie weiterhin in Balance zu halten, und prinzipiell nichts zu überstürzen. Ein Optimismus, der in der Erinnerung daran gerechtfertigt sei, dass es die Menschheit, im Laufe der Geschichte, immer wieder geschafft habe, Lösungen für gravierende und existenzbedrohende Probleme zu finden.

Optimismus

Optimismus ist im Bezug auf die Klimakrise zweifellos von großer Bedeutung. Um gegen das von Expertinnen und Experten prognostizierte, bevorstehende Klimachaos und gegen die damit verbundene Bedrohung unserer Zivilisation und Existenz anzukämpfen, muss die Hoffnung bestehen, dass es nicht schon zu spät sei; dass das von uns entwickelte System sowie die Mächte, die es steuern, noch geändert und umgelenkt werden können; dass wir noch die Möglichkeit haben, etwas zu verändern.

Optimismus und Hoffnung werden im Volksgebrauch oft als Synonyme behandelt. Beide Begriffe beziehen sich auf den Wunsch eines bestimmten, zu erwartenden Resultates. Doch während Hoffnung oft auch unabhängig von Wahrscheinlichkeitseinschätzungen bestehen kann, basiert Optimismus generell auf der Beurteilung bestimmter Gegebenheiten. Diese Beurteilung ist oft von Erfahrungen geprägt, die in der Vergangenheit mit vergleichbaren Situationen gemacht wurden.

Das Argument, Optimismus in der Klimapolitik müsse bestehen, ist demnach prinzipiell ein wichtiger Beitrag zum politischen Dialog unserer Zeit sowie ein fundamentaler Moment der Lösungsfindung. Es stellt sich jedoch die Frage, wann dieser formale Optimismus letztendlich zur Aktion führen muss, um bestehen zu können. Denn, haben wir, die Menschheit – die Expertinnen und Experten – nicht bereits Lösungen zur Bekämpfung dieser größten Bedrohung unserer aller Existenz gefunden? Wissen wir nicht bereits, was zu tun ist, um dieser Krise zu entkommen und somit den Optimismus zu rechtfertigen? Müssen wir nicht, einfach oder endlich, in Aktion treten?

Krise

Das griechische Wort „Krisis“ signalisiert einen Wendepunkt. Nur in Zeiten einschlägiger Krisen, werden große, soziale Umstellungen in die Wege geleitet. Die Verfolgung einer eher moderaten, traditionellen und persistierenden Klimapolitik bedeutet wohl, dass die Krise zwar in Aussicht, aber – zumindest in unseren Breiten – noch nicht allgegenwärtig ist. Dass wir, in unserem Land, noch nicht das Gefühl haben, aus letzter Not agieren zu müssen.

Der Optimismus, von dem Kurz spricht, signalisiert, dass wir bis zum Moment der radikalen Änderung noch Zeit haben. Allerdings, wenn wir den Expertinnen und Experten unter uns glauben wollen, scheint sich diese Zeit laufend zu verkürzen.

Die Geschichte hat uns tatsächlich gelehrt, dass wir es bis heute, von den immerhin massiven Opfern abgesehen, immer wieder geschafft haben zu überleben. Aber das bedeutet nicht, dass wir unsterblich sind. So hat Nietzsche einmal geschrieben: „Gewiss, wir brauchen Historie. Das heißt wir brauchen sie zum Leben und zur Tat, nicht zur bequemen Abkehr vom Leben und von der Tat.“

Hausverstand

Eine interessante Wortwahl in Kurz’s Beitrag zur Klimapolitik ist ferner jene des Begriffs des Hausverstandes. Dieser signalisiert, in erster Linie, eindeutige Parallelen zur (Haus-)wirtschaft und impliziert, dass die Wirtschaft dem Kampf gegen das Klima nicht zum Opfer fallen darf.

In zweiter Linie bezeichnet Hausverstand jedoch auch etwas immanentes, etwas bestehendes, was man von Haus aus besitzt.

Es ist unumstritten, dass Österreich den Klimawandel nicht alleine bewältigen kann. Die dafür notwendigen wirtschaftlich-sozialen Umstellungen müssen auf globaler Ebene und innerhalb einer europäischen und folglich internationalen Kollaboration erfolgen. Für eine solche Kollaboration braucht es Vorreiter: Nationen, die den Mut und die Ressourcen besitzen, die ersten Schritte in die Richtung eines kollektiven, globalen Zieles zu setzten. Dies setzt natürlich die Bereitschaft voraus, gewisse Verluste zu verzeichnen, sowie auch Optimismus und den Willen, unsere intellektuellen, praktischen und sozialen Kapazitäten zu überdenken, zu erneuern und zu erweitern. Hausverstand alleine wird dafür nicht ausreichend sein.

Autor/in: B. Weber

//////

Optimism and “Hausverstand” in climate politics

When it comes to climate protection, according to the CCPI, Austria performs significantly worse that its European neighbours and even lies far behind China. Can optimism in a climate politics based on “common sense” still be justified?

The recently published CCPI (Climate Change Performance Index) evaluates Austrias performance in the matter of climate protection as significantly worse than China’s and the European average, and hence downgrades it to place 38. Austria’s president Alexander Van der Bellen emphasised that an adequate climate politics must be in the centre of Austria’s recently inaugurated government. Austria’s new and once-again chancellor, Sebastian Kurz, defended his stances regarding climate politics, already during his election campaign, repeatedly with both the terms “optimism” and “Hausverstand”, the latter being a German term that often might be best translated with “common sense”, yet implies a broader meaning. The sort of Hausverstand Kurz advocates is supposed to keep ecology and economy in balance and to urge us “not to rush into something”. Moreover Kurz repeatedly justified his proclaimed optimism by reminding us, that human beings, during history, always managed to find solutions for serious and life threatening problems.

Optimism

Optimism, with reference to the forthcoming, not to say current climate crisis, is beyond doubt of great significance. In order to combat climate chaos and the related threat of our civilization and existence, which are predicted by experts, hope must persist that it is not too late, and that the system we invented, as well as the powers that lead it, can still be transformed.

Optimism and hope, in common language, are often treated as synonyms. Both terms refer to the desire of a certain, expected result. Yet while hope can often persist independently from evaluation of probability, optimism generally relies on the assessment of certain conditions. This evaluation often is affected by the experience one previously had with comparable situations.

The argument, optimism in climate politics must persist – and that we thus should not give up yet – is hence both an important contribution to the political dialogue of our times and a fundamental moment of finding (or inventing) the solution. However, we must ask: when does this formal optimism need to evoke action, in order to persist? Kurz is optimistic that we will find solutions to the problem, but haven’t we, the human beings – or rather the experts among us – already found solutions? Don’t we already partially know what needs to be done in order to survive, and may we hence, precisely because of those proposals of solution, justify our optimism? Don’t we just need to spring into action?

Crisis

The Greek word “Krisis” refers to a turning point. Only in times of great crises, significant social transformations use to take place. The pursuit of a rather moderate and traditional climate politics could mean, that a crisis might be in view, but – at least from our view point – not (yet) omnipresent. It affirms that we do not feel the urge just yet to react to what might be interpreted as an emergency.

The sort of optimism Kurz advocates, implies that we do still have time until we need to make some radical changes. However, if we choose to believe a great number of experts among us, this time appears to be constantly decreasing. History indeed taught us that – leaving aside the massive number of victims – human beings have always managed to survive. But this does not mean that we are immortal. As Nietzsche once wrote: “We need history. That is, we need it for life and action, not for a comfortable turning away from life and action.”

“Hausverstand”

The second term, Kurz repeatedly associated his stance on climate politics with, is the German word “Hausverstand”, literally home-intellect. That is, in more than one occasion Kurz confirmed that he wants to pursue a climate politics based on “Hausverstand”. This term, which might occasionally be best translated with “common sense”, on the one hand, shows distinct parallels to the term “Hauswirtschaft”, economy (of the house or home), and thus implies that the economy must not be the victim of climate politics. On the other hand, “Hausverstand” further relates to something intrinsic and persistent, to something one has “got from home” and thus was born with or grew up with.

It is indisputable that economic and social transformation has to occur on a global level, hence within a European and international collaboration, and thus cannot lie on the shoulders of one single nation. However, yet needless to say, in order to take action and give life to such a collaboration, we need pioneers: nations with courage and the resources to make the first pertinent steps towards a collective, global goal. This obviously presumes the readiness to take on certain losses and sacrifices, as well as optimism and the will to rethink, renew and extend our intellectual, practical and social capacities. “Hausverstand” alone won’t be sufficient.

Author: B. Weber

Comments are closed